HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

There is no doubt that the sword was an important military and cultural icon in the lives of the first Scottish Highlanders. Carved representations of Scottish swords have been found in many parts of the Highlands, including on early Medieval tombstones and effigies from the islands of Oronsay, Islay and at Kinkell Kirkyard, on the mainland. The influence of the Viking sword is also clearly evident as many of these Medieval stones depict hilts with a lobated (rounded or grooved) pommel and slightly inward curving quillons. Occasionally, they also show spatulate or flattened hilt finials. Blades are wide, double-edged and with single-handed grips.

It is not unreasonable to conclude that following continuous Scandinavian invasions and the later settling and assimiliation of these Nordic peoples in Scotland (particularly its outlying islands), the swords carried by Scottish Highlanders from the turn of the first millenium (1000), would be strongly influenced by Viking sword design and manufacture.

At this early stage, a uniquely Scottish style cannot be fully discerned, as many hilt variations are known to have been carried throughout Europe during the following centuries. It is only as we move beyond the Medieval period that more defined and peculiarly Scottish hilt forms emerged, becoming more familiar to the modern eye.

Despite the common representation of the sword within Gaelic culture, the Medieval Highland warrior was not primarily a swordsman. Indeed, during the numerous conflicts with England and regular inter-clan disputes of the Medieval era, the Caledoni or Scotti were predominantly spear or pikemen and fought in large groups or schiltrons. Bitter conflict with the English Crown and the gradual subjugation of the Scottish Lowlands, meant that the Highlanders literally retreated to their northern ancestral areas and concentrated on establishing and defending their own lands from rival clans. This resulted in a more “personal” and small scale type of warfare where the clan chief was expected to lead his men into battle and be the first to expose himself to the enemy.

Occasionally, he would also have to prove his social status and heroism by engaging in duels between other chieftains. The use of long pikes or spears in a duel was deemed impractical and eventually the broadsword and small shield (targe) became the favoured combination used by the Highlander. It was to remain so for many generations.

THE TWO-HANDED BROADSWORD

Scottish broadswords of hand-and-a-half or two-handed form began to appear in the 15th Century and until recently, were routinely described by the term claymore or claidheamh mòr (“the great sword”). This has now been disputed by several respected authors, including Claude Blair and David Caldwell. The correct Gaelic pronunciation is now thought to be claidheamh dà làimh (“sword of two hands”). The term claymore (claidheamh mòr) should therefore be used only to describe the later basket-hilted sword.

Irish mercenaries in the pay of Elizabeth I (1533-1603) are known to have carried these ‘great’ swords whilst campaigning in Ulster (1594-1603). Contemporary accounts also describe how they were slung on the back and sheathed. Continental mercenaries such as the Landsknechte also carried a larger, two-handed sword, preferring no scabbard. They also held the sword more comfortably at the slope.

The two-handed sword (or “twahandit” in Lowland Scotland) was carried from the beginning of the 16th and well into the 17th Century, only being superceded towards the end of the century, by the Highland basket hilt. Due to their huge size, these swords would have taken great strength and skill to wield effectively in a melee. The demoralising effect on any enemy when confronted with a group of screaming Highlanders brandishing these huge weapons would have been obvious and devastating. There are several types of this sword.

The Two-Handed Sword – type 1 (claidheamh dà làimh)

The Highland two-handed sword (claidheamh dà làimh) or ‘twahandit swordis’ emerged at the beginning of the 16th Century and differed from continental two-handed swords of the period in a number of distinct ways. This included a slightly shorter blade and the absence of parrying lugs normally found on contemporary ‘Landsnecht’(mercenary) two-handed swords. In many examples, the hilt has a pair of long quillons that incline towards the blade and terminate with quatrefoils. This quillon style is similar to earlier Scottish Medieval longswords represented on tombstones and reliefs found in Highland Scotland and clearly influenced by both the Gaelic and Viking artistic tradition. Pommels tend to be of simple wheel form and imitate the pommels of earlier Medieval Knightly swords. Another feature peculiar to this type of sword is the long langet that runs from the centre of the crossguard. It is sometimes either rounded or blunted at its point.

The Two-Handed Sword – type 2 (claidheamh dà làimh)

This distinctive and rarely encountered sword is occasionally described as being of ‘Lowland’ style in reference works, but there is no reason to assume that its use was restricted to any specific geographical area of Scotland. In reality it is likely to have been carried by both Highland and Lowland troops during the late-16th and early 17th Century.

The grip and pommel are very similar to the traditional claidheamh dà làimh or two-handed sword, although the pommel adopts a more European form and is slightly conical-shaped. Hand-and-a-half versions are also known of this sword. What makes this two-hander different to other ‘great’ swords of the period is the large, up-turned shell-guard and pronounced down-turned quillons. Blades are invariably of German origin and frequently stamped with the running wolf mark of Passau or Solingen. This sword type does not have the fluid beauty of the claidheamh dà làimh and very few examples have survived.

The Lowland or ‘Landsknecht’ Sword

This style of sword is clearly of North European and not Scottish lineage. It is of a type that has its origins in the north of the continent, particularly Switzerland or Germany, and is more commonly known as the weapon of choice for the ‘Landsknechte’ (or mercenaries), who offered their military services throughout Europe during the 16th and early 17th Centuries. The Scottish Highlander willingly adopted these two-handed battle swords and they would have been carried alongside the more traditional Scottish claidheamh dà làimh.

The general hilt and blade characteristics include quillons of flat, ribbon-like section and distinctive fleur-de-lys terminals. Parrying hooks are also present on straight, double-edged blades. Grips tend to be long, occasionally waisted and covered in leather, with a wooden core.

THE BASKET-HILTED BROADSWORD

Although it is widely assumed that the basket-hilted broadsword is a purely Scottish invention, contemporary evidence and surviving examples contradict this common assumption. Basket-hilted swords were already widespread in Northern Europe (particularly Germany, Switzerland and Scandinavia) from the early 1500’s, and their introduction coincided with the growing obsolescence of full armour (including armoured gauntlets) and the practical need to arm oneself with a sword that had an enclosed hilt affording robust protection to the exposed hand. They were a simple adaptation of the earlier Medieval cross-hilted broadsword, with the addition of extra bars and simple plates. As the 16th Century progressed, the hilt profile became more complex and elaborate combinations of bars and plates were added. The use of a series of flat or slightly rounded, intersecting bars, strengthened with small hilt plates became commonplace. Blades were normally double-edged and meant for cutting (in contrast to the contemporary fashion for thrusting, rapier blades), and it is thought that these practical swords would have been employed in battle where their robustness was relied upon.

Detailed historical evidence as to why the basket hilt became so closely associated with the Scottish Highlander is not conclusive but what is known is that numbers of Scottish mercenaries who fought for the English during the late-16th Century, brought back to Scotland quantities of English-made basket-hilted swords and they soon became popular in the Highlands. English writers of the time referred to this type of hilt as being of “Irish” style. Scottish writers also began to describe them as “Highland hilts” or “Highland Guards”.

As the 17th Century progressed and the basket hilt evolved, the specific arrangement of the hilt bars and appearance of wider hilt plates (with guards in the style of St Andrew’s crosses or saltires) point towards an emerging “Scottish” style of basket hilt.

There are a number of other key design features that differentiate early English and Scottish basket hilts. One of the most notable is the development of distinct pommel shapes. English basket hilts of the early 17th Century adopted large, apple-shaped or rounded pommels that eventually developed into more ovoidal or bun-shaped forms by the end of the century. The pommels on Scottish basket hilts were invariably of conical or ‘plumet’ shape, sometimes with deep grooving and prominent tang buttons.

Hilt styles were also changing. English swords displayed a more open basket, with fewer and thinner hilt bars than their Scottish counterparts. Scottish basket hilts incorporated more hilt bars and plates and from the early 1600’s, developed a distinctive “enclosed” form, with flattened bars and pierced hilt plates. The Scottish basket hilt was also of a generally higher standard of manufacture.

When Scottish Highland sword types were gradually replaced by the basket hilt in the 17th Century, many earlier two-handed sword blades were simply removed from their original hilts and attached to new basket hilts. This explains why much older blades are sometimes found in later basket hilts.

The sourcing of robust sword blades was crucial to the success of the Scottish basket hilt and Scottish hilt makers had known for many years that the best blades were manufactured on the continent, particularly Germany, Spain and Italy.

Most Scottish hilts dating from the mid to late-17th Century are matched with German blades, many bearing the spurious name ANDRIA(or ANDREA) FERARA (FERRARA). This Italian sword maker was renowned for the quality of his sword blades and his name was used by other, non-Italian sword blade makers to endow an aura of high quality. These wide, flexible, multi-fullered and double-edged fighting blades were devastating close combat weapons on the battlefields of Scotland and England.

BASKET HILT TYPES

THE WHEEL POMMEL HILT

These distinctive basket hilts were popular for a relatively short period of time (c.1600-1650) and although they are normally viewed as being uniquely Scottish, it is likely that they were carried by both Scottish and English troops. The design feature most associated with this sword type is a flat “wheel” pommel, large tang nut and small hilt panels attached to vertical bars.

THE RIBBON HILT

The Scottish ‘ribbon-hilted’ or ‘beak nose’ basket hilt is one of the earliest “Scottish” sword types and was unique both in terms of design and method of construction. The historical origins of this sword are not clear but similar enclosed hilts formed from flattened hilt bars are noted on both English and German broadswords of the late-16th and early 17th Century. These swords normally exhibit long, counter-curved quillons that are absent in Scottish ribbon hilts. It appears likely that Scottish sword makers simply took this form of hilt (probably brought to Scotland by Scottish mercenaries fighting in both mainland Europe and Ireland) and made it their own, with a number of distinctive refinements.

The first ribbon hilts comprised hilt bars of flattened steel strips that were deliberately ‘pointed’ at the end in order that they could be inserted into deep holes cut into the large pommel. This added greater strength and stability to the basket and differed from many contemporary English basket hilts, where some of the hilt bars are left short of the pommel and not inserted, thereby reducing its inherent rigidity. Later ribbon hilts (post-1650) differ by having the upper end of the guard joined to a flat semi-circular slot deeply cut into the middle of the pommel.

In design terms, the ribbon hilt has a number of characteristics not found on other Scottish basket hilts. This includes the absence of forward-guards and the addition of of a triangular guard that links two saltire-bars towards the pommel and is present near the blade. The early hilts also exhibit a pair of recurved quillons to either side of the hilt that appear to be a throwback to the late-16th Century.

Later hilts removed these quillons, replacing them with the familiar ‘beak nose’ projection. Additional rear-guards are consistent with later models and appear to be a deliberate incorporation of the attributes of the more standard Scottish basket hilt. Very occasionally, a ribbon hilt is found with its original black japanning (varnish), a method of protecting the hilt from the harshness of the Scottish climate. Unfortunately, most have lost this finish due to the vagaries of rust and overzealous cleaning by subsequent generations.

© Harvey Withers Military Publishing, 2024

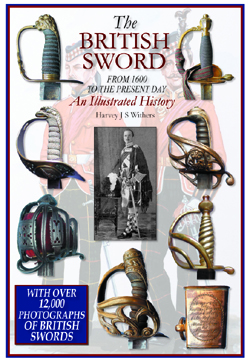

Taken from The British Sword – From 1600 to the Present Day – An Illustrated History by Harvey J S Withers – 12,000 full colour photographs – 884 pages

For more details please click on the images.